Scapegoat is a tabletop murder mystery ARG.

Set in a hospital, Scapegoat takes the players through a physical and digital journey as they roleplay as a nurse, department head, janitor, or doctor’s spouse, working to uncover the mystery behind the death of a resident physician. Players can scan QR codes that lead them to tinychoice games that provides them with bits of information about who they are and what their character is doing at the current moment. At the end of the tinychoice game, the player is directed to a physical location in the playspace where they can find a “tableau” piece: a wooden puzzle piece that reveals something that occurred in the characters’ past related to the murder. The end goal of the game is for players to come together to uncover the murderer or— if they’re the killer— to pin the murder on someone else.

My Role

Designed game mechanics, including the usage of individualized tinychoice clues, collaborative tableau segments, and the physical space as gamespace

Created overarching narrative, prototyped individual clues, and edited tinychoice clues

Delineated, illustrated, and fabricated tableau puzzle pieces

Prototyping & Playtesting

Our initial idea for Scapegoat was a two-player interactive installation combining projection mapping, physical computation, and a dating simulator game to emulate the experience of stalking and being stalked.

Each player’s existence would have been unbeknownst to the other. One player— the one playing the victim— would have an interactive experience with the room that they are in. Each interaction and action that the victim player did would be sent to the other player via a dating sim, and they would be able to comment on and impact said activities through the game.

Our plan was to modify the Bitsy game engine to program our game, and have it communicate with the projections in the installation via a web server. Since the fabrication of this would have been a big commitment, we initially decided to playtest the concept of a stalking game first, to confirm if this was the route we wanted to go with our project.

Prototype 1 & 2

Our first two prototypes involved our team playing deductive “stalking” games with each other.

Initially, we repurposed an anonymous chatroom one of our teammates had made, and tried to guess each other’s identities.

We quickly learned that:

Knowing the players made the experience more jovial and friendly than the unnerving and intimidating tone we wanted to reflect in our original idea.

The anonymous chat placed us all on the same level, and removed the inherent power dynamics we needed to recreate if we were going to use “stalking” as the basis of our project.

Our next prototype incorporated the physical aspect of our idea through a social-media-assisted game of hide and seek where both the “victim” and the “stalker” were hiding from and seeking out each other.

The stalkers— two members of our team— took pictures and videos of the victim and uploaded them to the Instagram account, which the victim could see.

This playtest revealed and reaffirmed that:

Demographics impacted how players felt about the experience; One of our teammates (male) expressed discomfort in playing a stalker because our victim player was a woman, and our victim player explained that she felt more comfortable playing because she knew her stalkers were fellow college students in her general age-range. While we were non-threatening as a team of majority-female college students, players that are more different than the victim demographically might have made our victim player less comfortable and more unwilling to play.

Recreating real-world power dynamics would make our game less appealing to many people. Most people wouldn’t be willing to play as a victim because they’re the only one vulnerable in that scenario.

Prototype 3

After much deliberation, we realized we couldn’t handle the topic of stalking with as much care as it needed in the timeframe we had and decided to pivot from our original idea. Rather than making an installation, we decided to focus on the playful, roleplaying aspect of our project to create a murder mystery game. We also maintained our core idea of mixing digital with analog in our game.

Instead of keeping our players in two separate, confined rooms, we decided to expand our playspace and have the game span our department’s entire floor. Our game board was a map of the floor abstracted into the environment of the story. Players received two types of clues: a personal clue the game master would provide them with, and an exposed clue each player had to seek out and bring back to the board, with the risk (or benefit, depending on the player) of other players being able to see the clue as well.

Our basic gameplay loop for each round of the game.

This iteration’s clues:

Personal clue: A flickgame players got by scanning a QR code. This game told players exactly what their character did before or during the murder through an interactive comic. At the end, they were prompted to find their collaborative clue in a particular spot in the playspace.

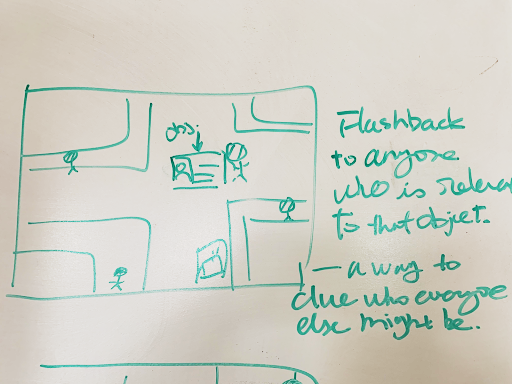

Exposed clue: An item from the story in their personal clue. When they brought it back to the board, it revealed a brief color-coded flashback of the overarching story in the form of a map that showed the characters that were relevant to the item.

The detective’s role card, from their first personal clue

The board with the flashback overview. Intended to be projection mapped, reactive to the touch of the exposed clue object.

Playtesting

We playtested our game in two rounds in our paper prototype. Our board, flashbacks, and physical items were made of paper, and we distributed the flickgame clues through links. This version of the game was set in a library, and involved murder and sabotage between friends, with the victim’s mother as detective.

Our paper prototype of our first murder-mystery iteration

During gameplay, players:

Weren’t able to complete their personal clues because they didn’t know the tapping mechanic behind flickgames

Were confused about what clue cards were

Didn’t interact much with each other initially

Had a hard time identifying what was happening or who they were in their personal clues

Spent more time piecing together what was going on collaboratively than competing with each other to find the killer (or defend themself if they were the killer)

Shared clues freely

Weren’t able to “kill” another player if they were the killer because they never had enough time alone with another player due to pacing

The detective demanded everyone show their clues immediately upon finding out their role

Takeaways:

Flickgames required more explanation on top of our game rules for players to understand them

We were too slow distributing clues, so players ended up staggered in each phase of the game, hindering their abilities to use mechanics like the killing mechanic

Two rounds was not enough time to create a complex enough narrative where every player could feel important or have stake in the game

Players needed to have deeper character backgrounds in order to get more into roleplaying and interact meaningfully with other players

The flashback maps and the personal clue anecdotes were redundant and confused players rather than giving them more information

The detective either had too much power over the other players, or was unnecessary as players shared information with each other anyways

Final Prototype

Our final game follows a hospital narrative full of deceit, blackmail, and murder. It includes 4 rounds where players navigate both the present and the past to uncover the mystery behind the death of one of the hospital’s physicians, Dr. Medulla.

Our basic gameplay loop, modified for our final version

Rather than a “personal clue” and an “exposed clue,” we split the two types of clues between the past and the present.

Players first started the game in the present. The DM, a private investigator in-game, explains that the players have been called to the P.I. office because one of the players’ in-game character suspected that Dr. Medulla’s death— which had been deemed a suicide by the police— was actually a murder.

We scrapped the mechanic of having different roles like “detective” and “civilian” because it overcomplicated gameplay and was unbalanced. In the final version, all players are on an equal playing field, and it’s up to their own deduction and acting skills to win the game.

Players choose their characters from:

Dr. Brum, the head of psychiatry at the hospital and the victim’s superior

Nurse Bellum, a close friend and coworker of the victim

Mr. Smith, one of the hospital’s janitors, who discovered the body

Kelly Brittle-Dura, the spouse of one of the hospital’s resident physicians, Dr. Dura. Their family is also suing the hospital in-game

After establishing which player is playing which character, players are handed costume pieces that identify them in the tableaus and a printed QR code that link to a tinychoice game. We chose to forgo flickgame clues in favor of tinychoice as they were both easier to create and more intuitive for players as it would rely solely on text and hyperlinks, which they’re already familiar with.

One of the spouse’s tinychoice clues. The missing gemstone is an important clue that can be a damning piece of evidence in the final round.

Each tinychoice game takes place in the present. Players are given insight into their character’s motives, defining character traits (that may serve as clues), and actions before, during and after the murder. These provide context for the player to understand their own place in the game and their relationships with other characters. They also establish knowledge their character would have in relation to the tableau pieces they’re to assemble together.

These tiny choice games prompt the players to go to specific locations on the map to find their tableau pieces, like their characters’ traveling to different locations in the in-game world. Each players’ tableau location was carefully selected so they wouldn’t accidentally find each other’s pieces, or they could encounter each other in certain rounds.

Our map, which we transposed onto our board.

A tableau is a theatre term for a still and silent scene. Usually, actors are frozen in dynamic positions, and it should tell a story in a single image. Since our game was already quite theatrical, I thought emphasizing the theatre influence by incorporating tableaus at the climax of each round would help create tension for players and encourage them to use their tinychoice clues to inform how they interpreted the bigger picture of the case.

For Scapegoat, the tableaus are in the form of illustrations. Each player collected a piece of the tableau, and assembled them together like a puzzle. Once assembled, the completed tableau revealed an event related to the case. This event took place in the past, before the investigation began. Players’ jobs then were to come to some sort of conclusion about the case.

The first two tableaus are straightforward. They establish basic clues: Dr. Medulla was pushed off of the hospital roof, and Kelly’s sibling died after Dr. Medulla signed off on their release from the hospital the day after they had a failed suicide attempt.

The last two tableaus have the opportunity to be tampered with by players. They both have real and fake piece(s) that can be swapped out based on their choices in the tinychoice clues.

Dr. Brum and Kelly have the opportunity to blackmail or bribe Nurse Bellum and Mr. Smith respectively within their tinychoice games. If they choose to do so, the blackmail/bribe recipients will receive a different QR code— Nurse Bellum in round 3 and Mr. Smith in round 4.

Dr. Brum’s first tinychoice clue. They can choose to blackmail Nurse Bellum or not in order to hide their involvement in a drug smuggling scheme, and hide a motive for murder.

Nurse Bellum’s third tinychoice clue. When they go to find their tableau piece in the Courtyard, they have a choice for which piece to take back— a real or a fake piece.

The third tableau completed. Nurse Bellum’s piece can either tell the truth— where Dr. Brum catches them stealing drugs and stays silent in exchange for money— or blame Mr. Smith. Both versions have the perpetrators caught by Dr. Medulla, giving them a possible motive for murder.

Mr. Smith’s fourth tinychoice clue, where they can choose to accept Kelly’s bribe or not. This choice determines where they can go to pick up their tableau piece.

The fourth and final tableau completed. If Mr. Smith declines Kelly’s bribe, their tableau piece will reveal that Kelly was the murderer, backed up by the image of their wedding ring on their hand as they push Dr. Medulla to death. If Mr. Smith accepts the bribe, their tableau piece omits the ring, and it’s up to the players to make their case for who committed the murder.

Playtesting:

In our initial prototype for this version of the game, we only playtested the first two rounds. Players noted that:

Coming in and out of the same room felt like a chore, since the part they most looked forward to was interacting with other players in the discussion section

The janitor in particular felt like they didn’t have much plot relevance compared to the other players

No one really understood Kelly’s relation to the patient in the second tableau until it was explained to them

Tableau clues were difficult to find, and sometimes members of our team had to assist players in finding them

They could figure out some of the plot without having completed the tableau, and would discuss with each other before every player had come back to the board

Some changes we implemented to address these in our final version were to:

Incorporate the bribing mechanic early on, so players felt they had more of a stake in the game

Painted the backs of the tableau pieces blue, so they stood out more to players, and adjusted the locations we put them in

Adjusted our narrative so each character had more connection to the case and each other (ex. Kelly was originally only related to the patient that died due to Dr. Medulla’s neglect, and is now also married to a resident doctor at the hospital)

Included the DM as more of a character (Billy Domicile, Private Investigator) to guide players through the rules of the game, provide the players with a more theatrical experience, and assist in making sure the bribing mechanic worked through QR codes

A photo from our last full playtest of Scapegoat